CONSERVING HARRY CLARKE

Three early stained-glass treasures in the National Collection

In 2023, Crawford Art Gallery successfully applied to The Heritage Council’s Heritage Stewardship Fund to ensure the long-term preservation and sustainable public display of three early stained-glass panels by celebrated artist Harry Clarke.

Significance

Crawford Art Gallery’s three panels of stained glass by Harry Clarke (1889-1931) are rare examples of the artist’s early training and emerging originality.

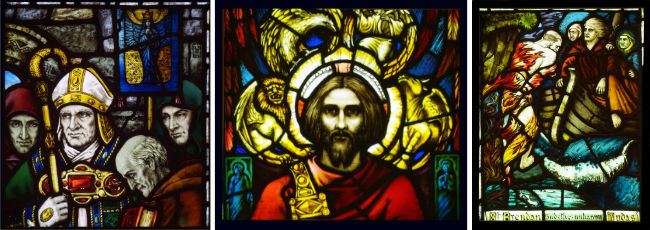

Purchased directly from the artist in 1924 through the Gibson Bequest Fund, The Consecration of St Mel, Bishop of Longford, by St Patrick, The Godhead Enthroned, and The Meeting of St Brendan with the Unhappy Judas were made between 1910 and 1911 while Clarke was a student at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art. He was awarded the highly coveted gold medal for these panels at the South Kensington National Competitions in 1911, at which work by students from England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland was adjudicated.

The panels offer evidence of Clarke’s emerging creativity in terms of colour, scale, design, and narrative. It is the inclusion of tiny saints or symbols, reminiscent of ancient Celtic carvings and illuminated manuscripts that demonstrates the artist’s interest in the Celtic Revival, and forecasts the inventiveness and originality in his later work.

Significantly, the lead that holds the glass in The Meeting of St Brendan with the Unhappy Judas (1911) follows the movement of the figures. Clarke’s early and exceptional use of lead in this work served to accentuate the tension in the story, and anticipated the artist’s extraordinary use of the material as both a vital structural element and imaginative support to descriptive detail, which he used to astonishing effect throughout the rest of his career.

Just a few years later, in 1915, Clarke installed the first of his commissioned windows for the Honan Chapel on the grounds of University College Cork, which secured his name as an expert in the craft of stained glass. He went on to create important commissioned works for public and private buildings throughout Ireland, England, and further afield.

In addition to these three works in stained glass, Crawford Art Gallery holds 23 of Harry Clarke’s works on paper, namely his pencil and watercolour studies for The Eve of St Agnes window and ink and watercolour drawings for the writings of Edgar Allan Poe and Robert Graves.

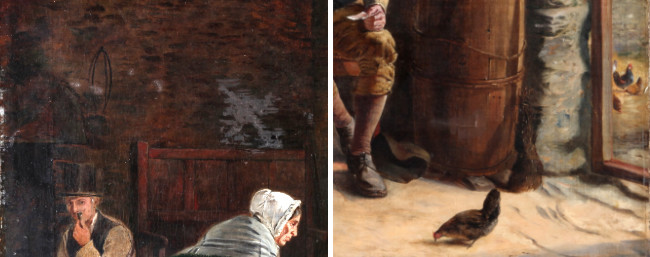

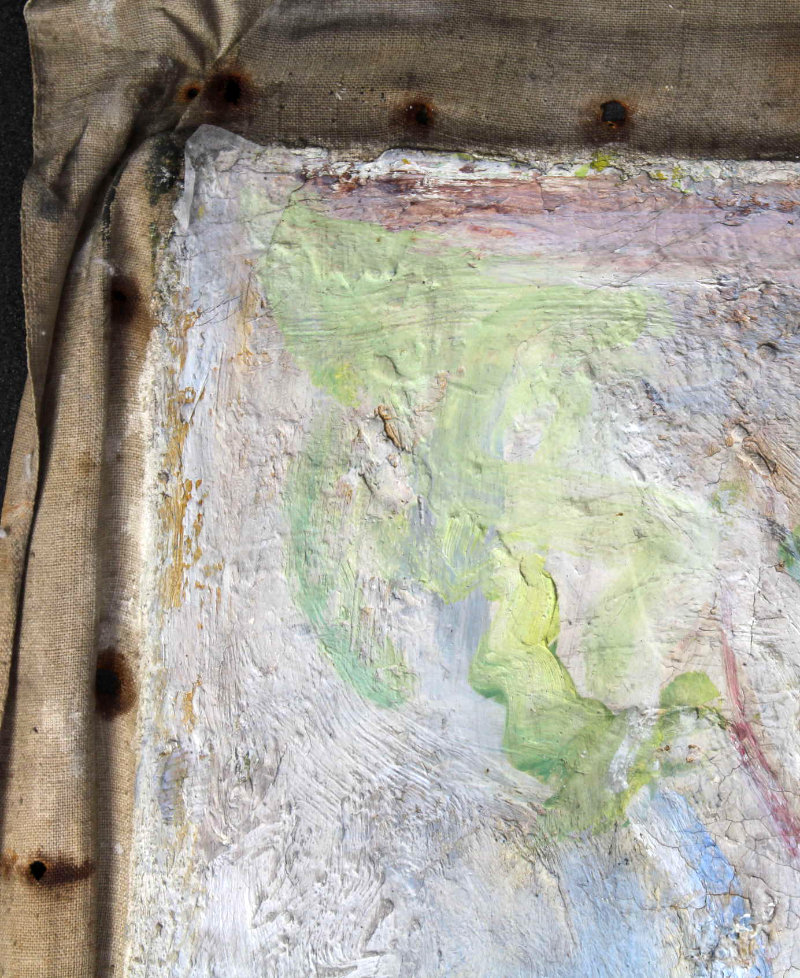

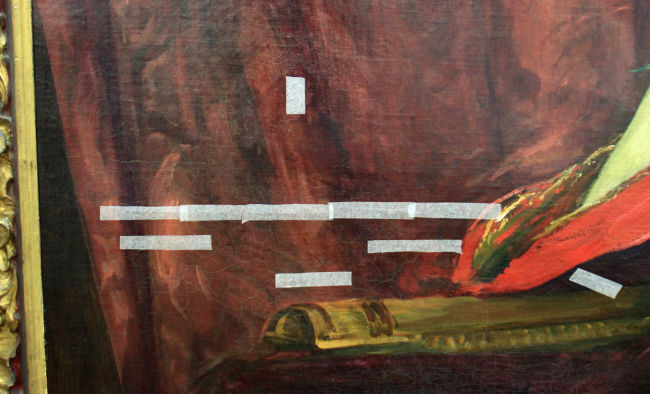

Current Condition

Since being acquired from the artist in 1924, these stained-glass panels have deteriorated, in part due to time, but also through historic poor handling and storage. This, combined with the effects of non-conservation grade framing units (containing heat-generating florescent lighting) have left the works suffering from accumulated dirt, damage, and cracking.

Assessment

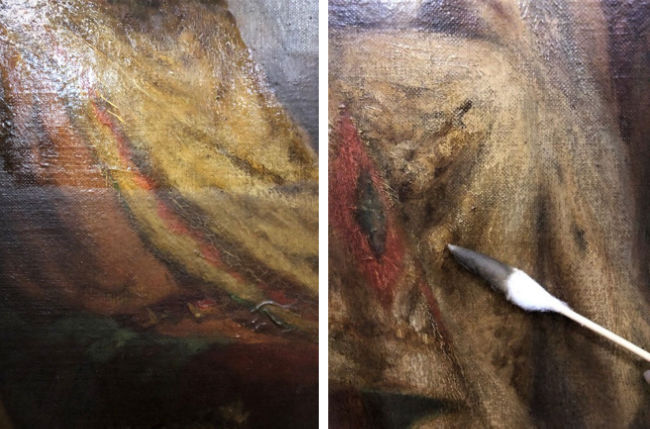

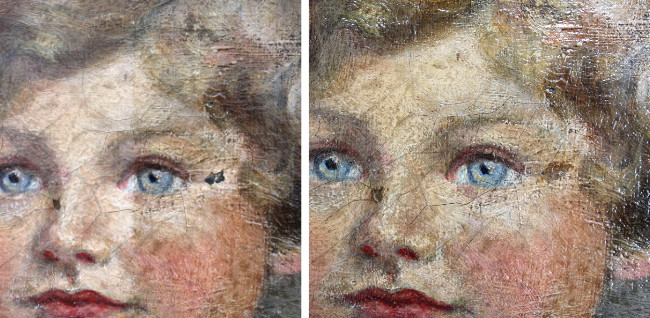

Following expert assessment, the three panels have been deemed to be at considerable risk. Initial cleaning was conducted in March 2023 ahead of more sustained conservation in August 2023.

The Consecration of St Mel, Bishop of Longford, by St Patrick removed from its old framing unit, March 2023. Photo: Michael Waldron.

Next Steps

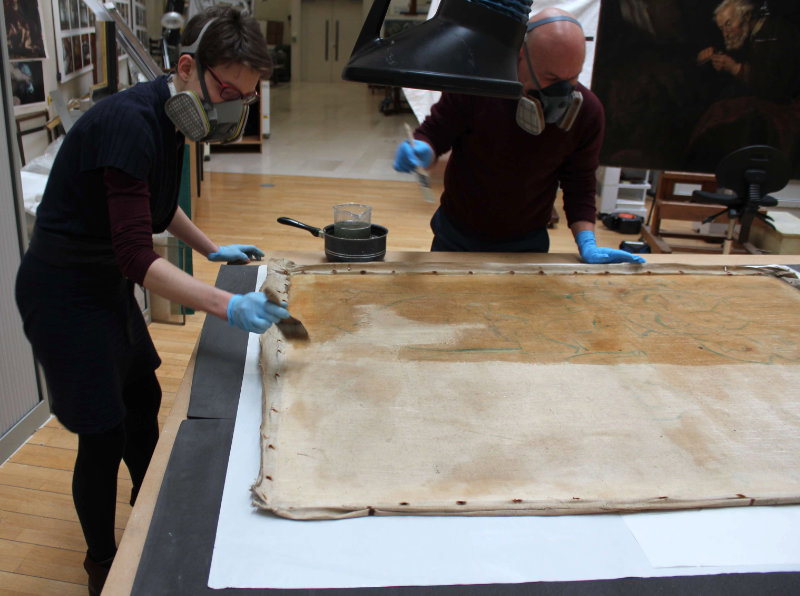

To coincide with National Heritage Week (12-20 August 2023), stained-glass conservator Philip Crook (Vitrail Studios) will conserve the three works at Crawford Art Gallery. They will then be fitted to new conservation-grade and custom-made LED backlit frames, which will enhance display potential into the future.

Free Public Talk

Join us at 1pm on Wednesday 16 August 2023 for a conservation talk by Philip Crook in the Lecture Theatre of Crawford Art Gallery.

Free | Book here through Eventbrite | All very welcome

Philip Crook at work.

This project is supported by The Heritage Council through the Heritage Stewardship Fund.

Text adapted from Reports by Dr Éimear O’Connor (2017) and Ann Chumbley (2023).