By Karl Schoonover (August 2020)

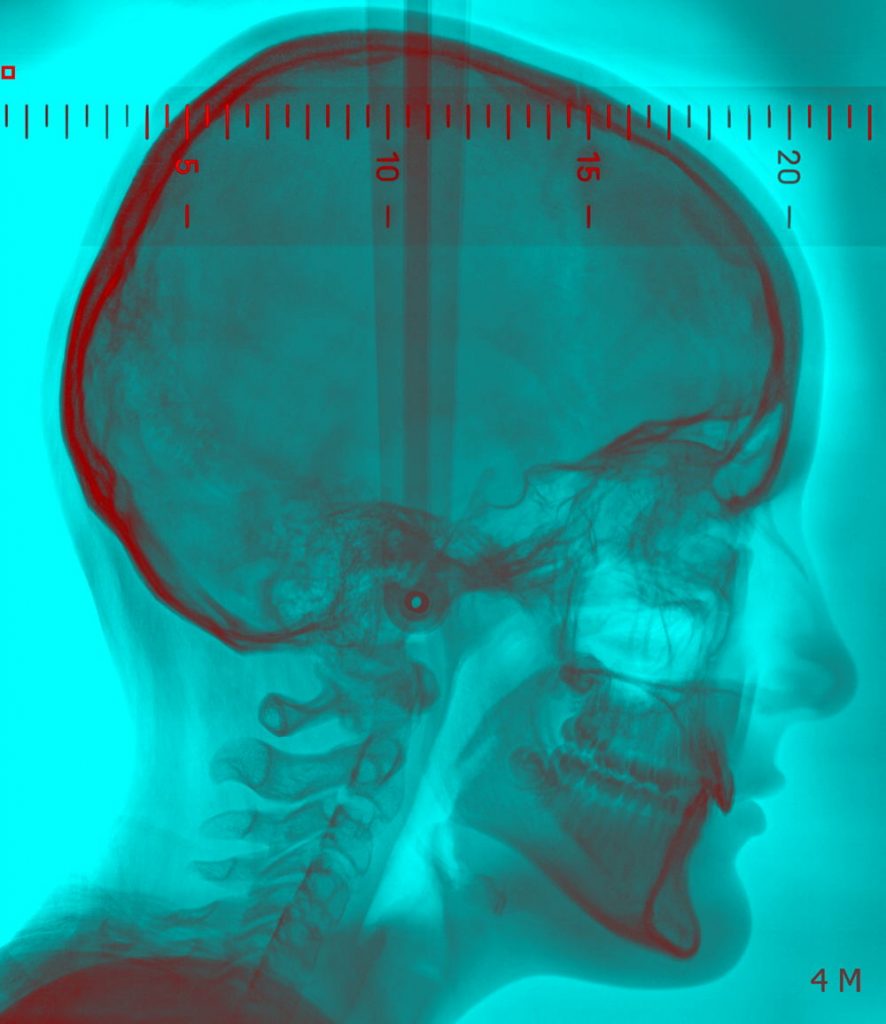

At the moment of writing this, I am asking myself, what has happened to the state? Has the state abandoned us? There have been moments this year when it has felt that we are governed by institutions that seem unconcerned with the inevitability of our premature death. In fact, during the current crisis’s early peak, some government officials of the world’s most prominent democracies appeared surprisingly public in their resignation to losing segments of the population. This period of history feels like an unsettling flashback, especially for queer and trans people who survived one of the last great pandemics, HIV-AIDS. Once again, we face gaslighting public discourses that obfuscate facts while allowing people to die. Being vulnerable and being a citizen seem increasingly incommensurate states of being.

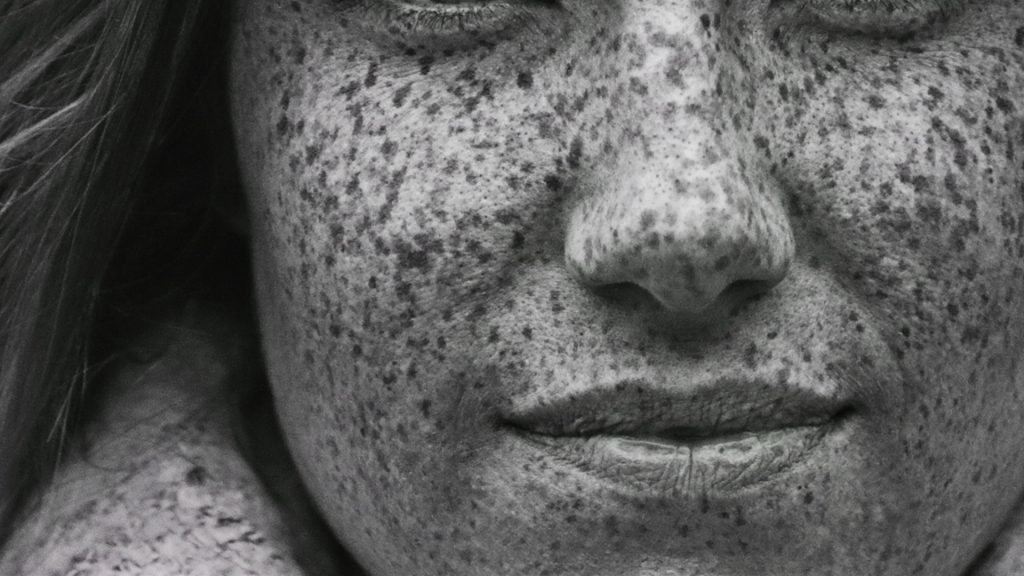

While completed before the current crises, Kevin Gaffney’s new work carries a prescience about our present moment. It forces us to confront rather than look away from the question of life within the modern nation state and outside it. It demonstrates the willingness of a state to jeopardize life to protect its future. From his earliest films, Gaffney has worked on refiguring the body politic. The speculative worlds he creates make havoc of the dominant institutions that yoke lived experience into conventional and orderly lives. Put another way, Gaffney is drawn to how queers experiment with ways to liberate their selfhood from the identity categories imposed upon them. Along the way, his work has resignified the messy bodies of post-conceptual art, offering a queer aesthetic formed around the visceral capacity to unhitch bodies from the reifying powers of identity that affix us to communities, genders, and the bodies we’re born in. In his latest work, Expulsion, he continues this project by asking about alternatives to current state formations, bringing to life a land where queer terrorists reinvent community around sex and gender dissidence. As with his other works, Gaffney fashions this imaginary realm from a textured history of institutions, traditions, and corporate capitalism. At one point in Expulsion, interrogators for the Queer State ask an asylum seeker for the name they would prefer if they were to be granted citizenship. The applicant responds, James Miranda Barry, a name many will recognise from Ireland’s queer past, as that of a 19th century doctor whose gender was assigned female at birth but lived as a man for their adult life. Another of those historical references for Gaffney’s Queer State is a late-twentieth century political movement called Queer Nation.

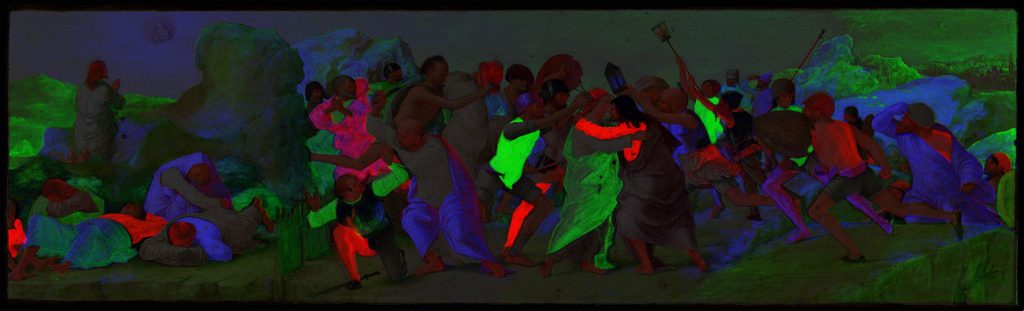

Queer Nation was formed around 1990 in the USA by some of the AIDS activists who had worked to establish ACT-UP and who decided to expand their protest agenda. Perhaps more loosely organised and less pragmatic, Queer Nation nonetheless borrowed the strategies that had made ACT-UP so successful: slogans with wicked wordplay, angry confrontation, joyous inversion of norms, and multifaceted shamelessness. In Expulsion, Kevin Gaffney imagines an ultimate expression of Queer Nation, a state formed of queers outside of heterosexual society, a mix of commune, sanctuary, and extremely exclusive gay ghetto. Is his invention, the Queer State, a utopian homeland or its quasi-fascist dark shadow? We are never quite sure.

Gaffney’s Queer State is a country founded by terrorists on the basis of their marginality and on the barren soil and scarred landscapes of extractive economies. Expulsion describes the process whereby refugees from other states can apply for asylum. This process involves an ideological indoctrination that freely incorporates queer retellings of patriarchal history, ecofeminism, anticorporate sentiments, and a loose neo-Marxism. As we observe the shockingly arbitrary process that grants asylum, we question the true nature of the community being formulated. When a Black applicant’s appeal for asylum in the Queer State is rejected, it feels inconsistent and cruel. The State tells him both that his mainstream character ‘would be considered a liability to our society’ and that his critique of corporatized consumer capitalism demonstrates ‘lack of compassion for [his] community’. Most troubling is the Queer State’s advice for his reentry into the non-queer world upon his forced, immanent return to it: adopt a non-confrontational attitude, embrace his masculinity, and aim for an individuality motivated by self-interest exercised in private. How could a radically humanist project expel an applicant only to return him precisely to the oppression it purports to oppose? Would an anti-hierarchal paradise demand such things? Offer such advice?

At several moments, as we question whether the Queer State is the anti-hegemonic community it purports to be, the film shifts gears, and intercuts sequences of video footage from the actual 1992 US presidential campaign of Queer Nation’s candidate, Joan Jett Blakk. Blakk is an African American drag queen who, at the time of the presidential campaign, had run for other public offices and would go on to be a member of the performance group Pomo Afro Homos. The documentation of Blakk’s campaign stump speeches comes in glorious imperfection, analogue video tape footage showing off an intentionally unpolished aesthetic. In this way, the shrill energy, playful scandalmongering, and sloppy fun of Queer Nation’s actual history erupts into the high-polish classicism of Expulsion’s Queer State. These two visions of queer disruption are brought side by side.

In the early 1990s, I was a young American queer coming of age who disidentified with the label ‘gay’. Queer Nation’s original call excited me for its refusal to settle for the begrudging tolerance afforded us by liberal heterosexuals (‘allies’ who had mostly abandoned queers during the HIV/AIDS crisis), its rejection of a minoritizing logic that condemned queers to the margins and had left us to die. Queer Nation rejected the impulses of conventional gay rights movements, spurning any politics striving for acceptance in mainstream society. It saw those who fighting for marriage rights for LGBT people as sell-outs, too willing to settle for an analogue of straight life and abandoning the radical potentiality of a life lived queerly. Today we would call Queer Nation’s resistance a campaign against ‘homonormativity’. But Queer Nation wasn’t just about complaint. It was also a beacon of unapologetic imagining, riotous anti-assimilationism, and a reclaiming of public space and the political sphere. At Queer Nation demonstrations I thought I detected the ascendency of a new political agency for LGBT politics, a promise that all citizens had the right to live, even in the most sexually dissident or gender non-normative way. While redressing the overwhelming dominance of heterosexual norms over life and dismantling patriarchal structures, the group was less conscious of how its particular forms of play and resistance were premised upon class privilege. This went largely unchecked in the group’s workings.

While the activities of Queer Nation regional chapters continue today, the group’s period of public national visibility dimmed by the mid-1990s, overshadowed by more mainstream fights for lesbian and gay legitimacy (e.g., demands for marriage rights) in a culture dominated by Clintonian compromise.[1] Queer Nation’s initial pronouncements, however, left us with questions that persist, and Gaffney’s Expulsion makes us confront those provocations: Can queerness be governed? Should it be governed? Can we imagine a mode of governing queerly? Will queerness ever find a place in statehood?

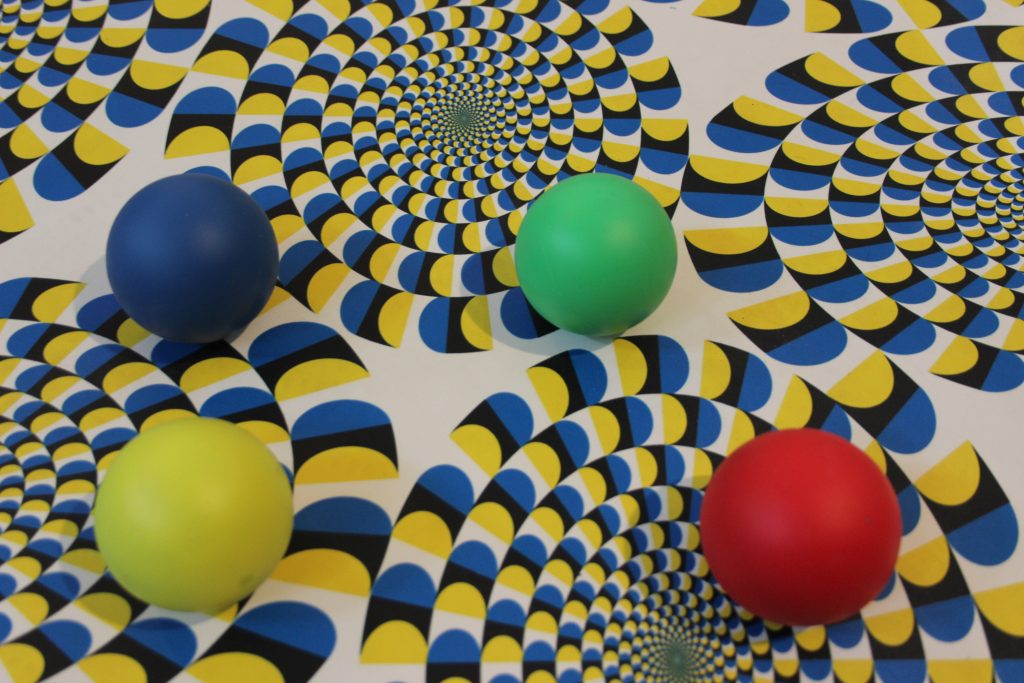

As a fantasy, Gaffney’s queer state intrigues the viewer with its volatile uncertainty. A satisfying queer heresy hovers in the Queer State’s declarations, including an overdue reckoning of history, a condemnation of the pink-washing of modern slavery practices, and a wonderfully concise critique of the patriarchy’s colonising of the concept of nature. However, Expulsion carefully avoids any full endorsement of the Queer State’s governmental operations, and it is not only through the juxtapositions of Queer Nation and this imagined state that the film foregrounds the Queer State’s ambivalent status. Beginning from its initial images, Expulsion performs its unsureness through an iconography of equivocal symbols. Take, for example, the flag paraded by a Queer State citizen through a depleted landscape. At the centre of the bright colours and triangle of the flag is a circular hole. Does this hole represent an empty duplicitous truth at the core of the Queer State’s project? Or is it that project’s acknowledgment of indeterminacy? A liberatory refusal to settle on queer identity? There are other startling images that lack full explanation, such as a uniformed body with a leather mask lying on a pile of rubble. This might be either a prisoner of the Queer State whose punishment reveals the hypocrisy of the Queer State’s project or simply a lovely pervert finally freely able to explore their sources of pleasure.

This unresolved ambivalence towards the Queer State’s justifications and its practices is kept crucially taut by Expulsion and, as such, it returns us to the dilemmas of the current moment. Why do we need a guarantee of the status quo’s persistence in the future in order to value human life in the present? Why do we need assurances of our own privilege in order to act humanely? Gaffney’s work does more than stage the incommensurability of a queer state; it shows us the dangers of not facing our own vexed relationship to being governed. One challenge of this moment is being able to imagine participatory democracy as something other than simply majority rule and to reimagine what a state can and should do for us.

Karl Schoonover writes about art, film, and other moving images. He teaches at the University of Warwick (UK) where he is Professor of Film and Television Studies. His most recent book Queer Cinema in the World (Duke University Press) was co-authored with Rosalind Galt.

[1]Two canonical accounts of Queer Nation from the early 1990s provide perspective on the group’s protest activities and a critique of its rhetoric: Lauren Berlant and Elizabeth Freeman, "Queer Nationality" Boundary 2 19.1 (1992): 149-80; Lisa Duggan, "Making it Perfectly Queer." Socialist Review 22.1 (1992): 11-31.