SCULPTURE SECRETS 8

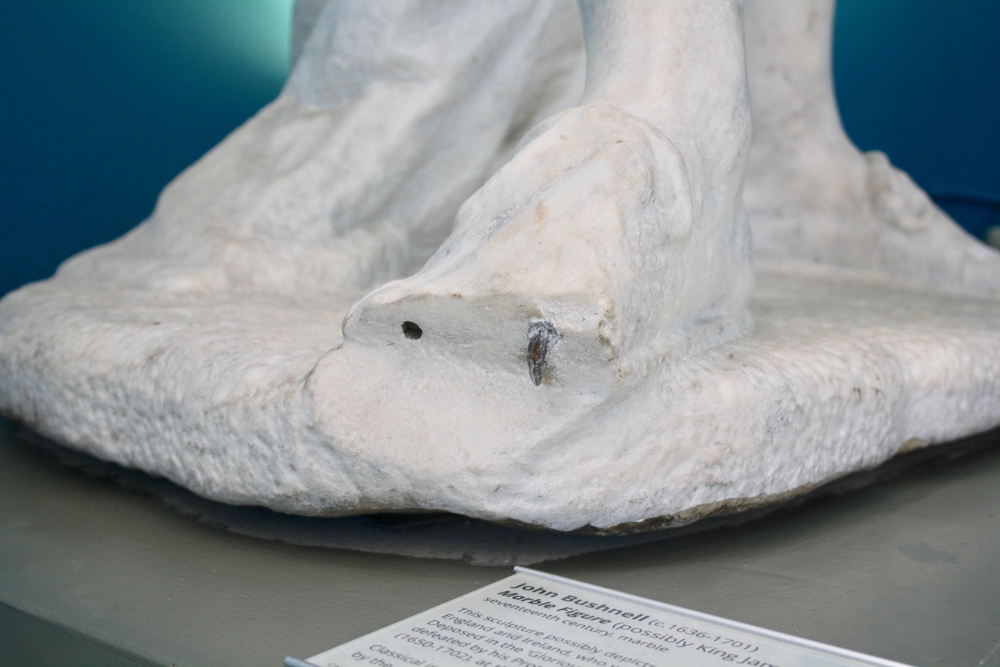

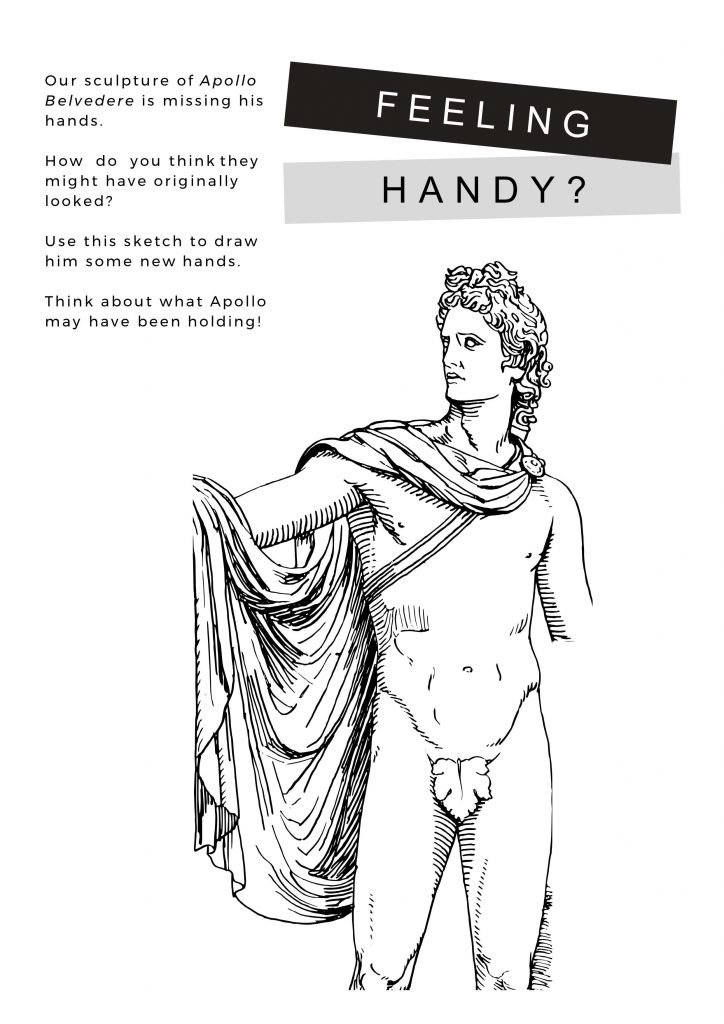

In this new 8-part series, we explore the stories of our Sculpture Galleries and uncover curious things that usually only curators get to see! Discover sculptors’ secrets and makers’ marks, focus on flashlines and fig leaves, and seek missing arms – and even extra feet – as Abbey Ellis traces the tales of our cast collection.

SCULPTURE SECRETS concludes with some personal reflections from our intern Abbey Ellis. She mulls over what her short time in the Sculpture Galleries has meant to her as both a scholar and reproduction lover.

A Love Letter to the Canova Casts

The past few months of staying at home have provided ample time for reflection. I can think of few places worthier of contemplation than the Crawford’s Sculpture Galleries. Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of spending a month and a half working in the space as part of an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) internship. My Irish adventure was cut short due to COVID-19 restrictions but my short time in Cork has still left an indelible mark on me.

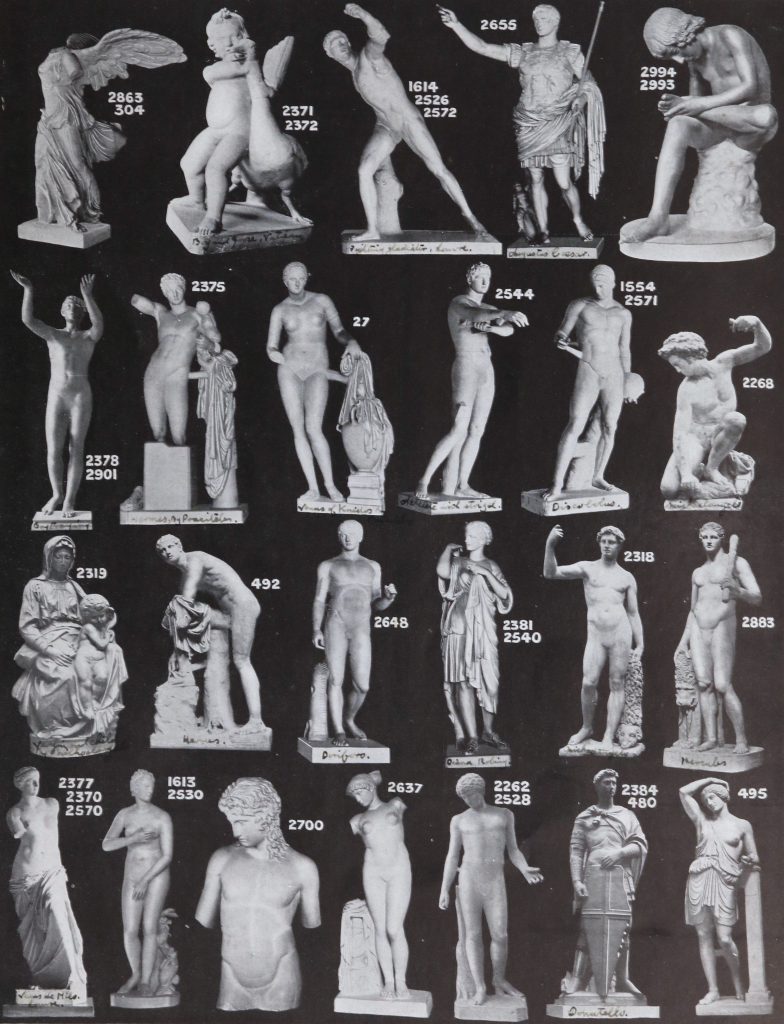

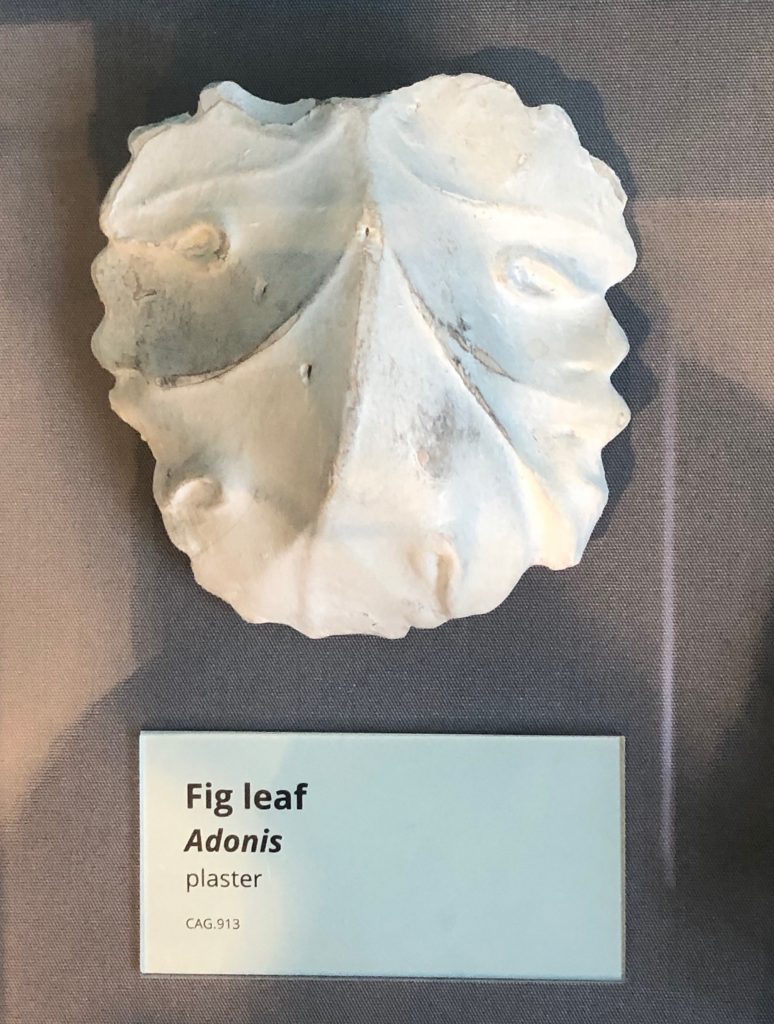

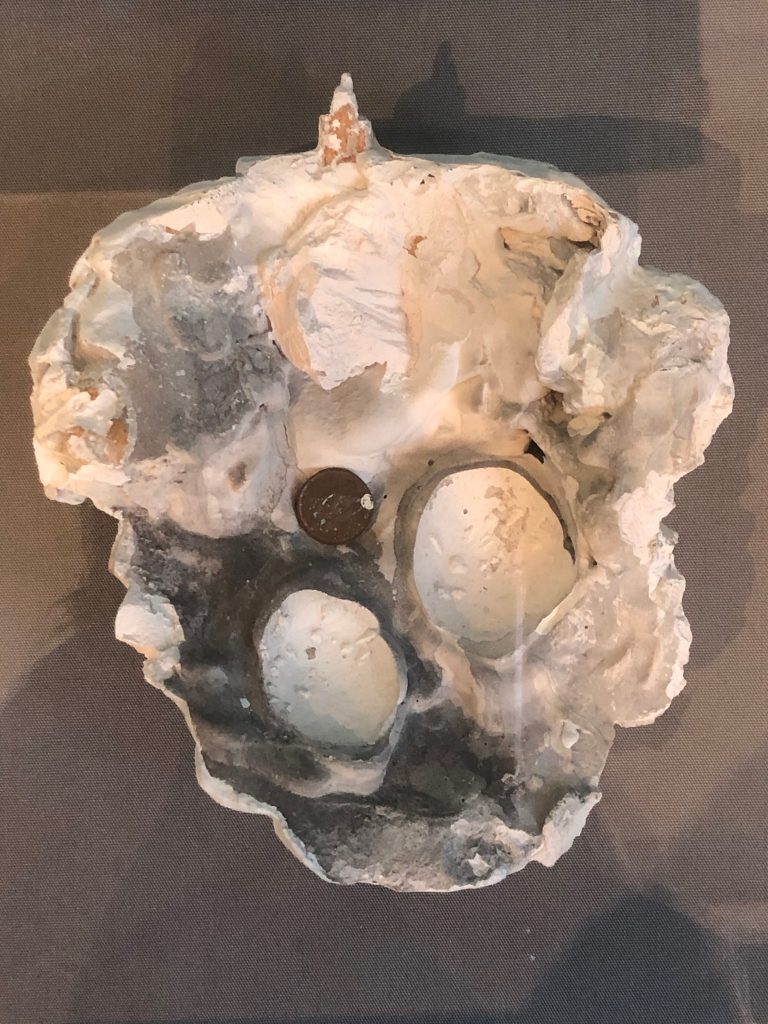

My PhD research is focused on plaster casts of ancient Greek and Roman sculptures, of which Crawford Art Gallery has a fine collection. Historically, casts have not been the subject of a great deal of scholarship, with “original” sculptures receiving the lion’s share of attention. But casts are truly fascinating! For me, the allure of the objects lies in the curious dichotomies that they embody.

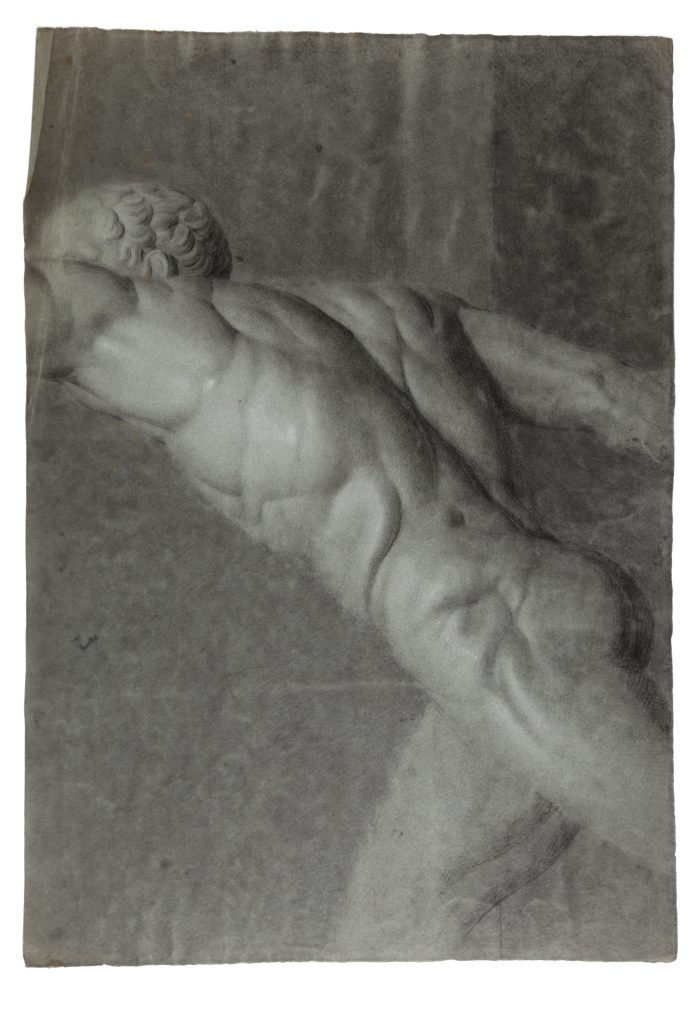

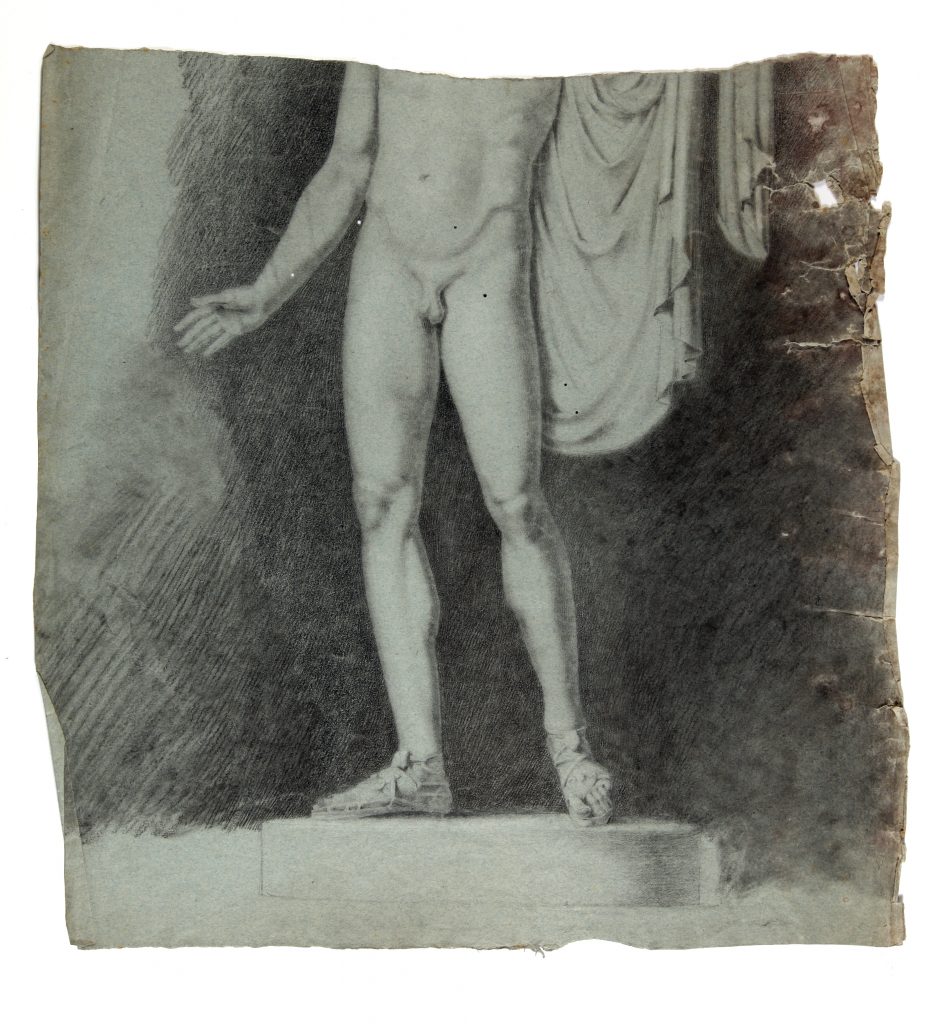

At once, casts are representations of older sculptures, often truly ancient works, as well as being skilfully made historical documents in their own right. They attest to how someone closer to us in time has engaged with a sculpture by producing a cast of it.

The dual identities of casts are inextricably entwined: the cast would not exist without the original precedent but at the same time, the original’s own history, reception, and popularity are very often shaped by the casts produced from them.

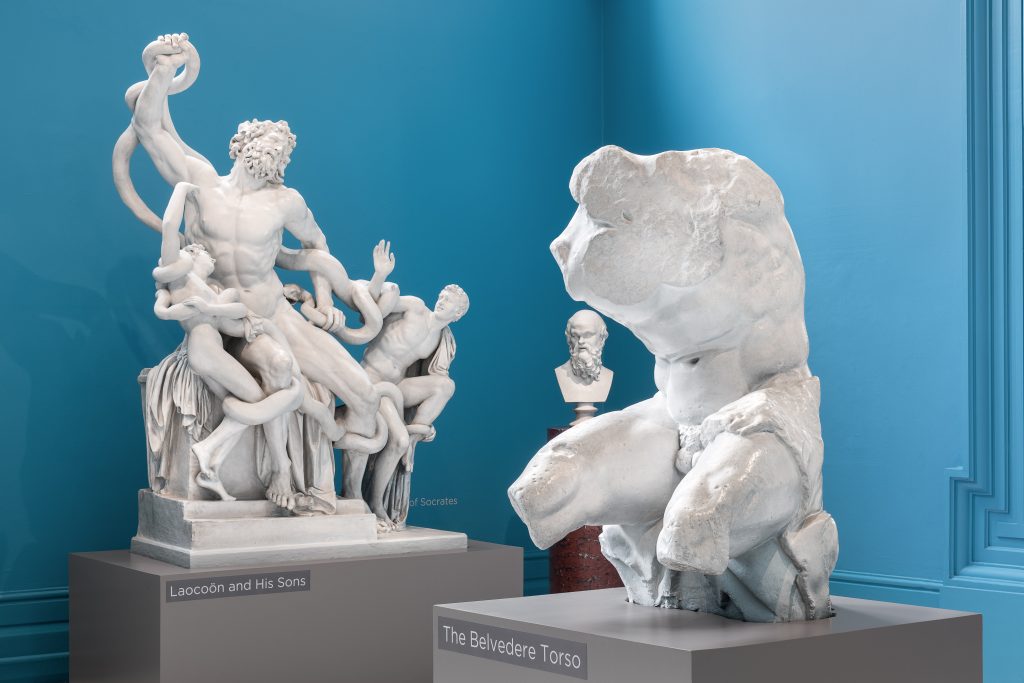

Casts are, clearly, inherently reproductive in nature, but very often their power to reproduce is often the only thing that marks them out as valuable. In very many museums, casts simply act as surrogates for the sculpture that they replicate. Crawford Art Gallery is particularly special for not considering its casts in this way.

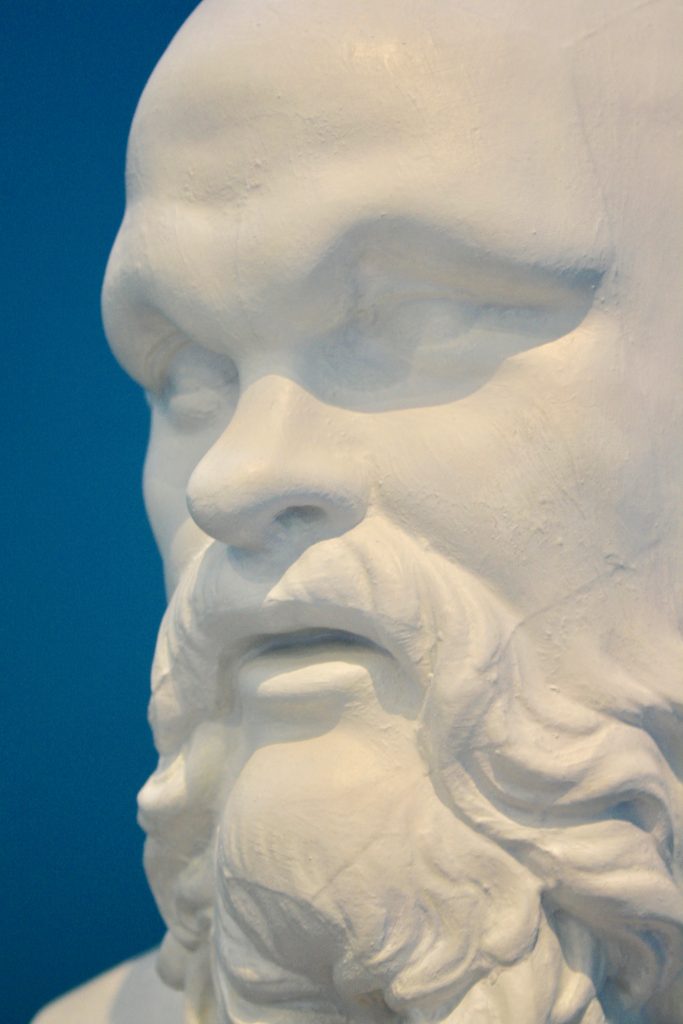

The subtle intricacies of the casts’ labelling demonstrate this perfectly. Often, casts are described in interpretive text as if they were the original sculpture. Explicit references to their “castness” are few and far between. Crawford Art Gallery’s casts, including the Boy and Goose displayed in the Half Moon Street window, are labelled very differently. Renowned London plaster caster Domenico Brucciani, the maker of the Boy and Goose cast, is listed front and centre at the top of the object’s label. The approximate date of the cast’s production is also given, information which is regularly missing from cast labelling elsewhere.

Framing Boy and Goose in this way enables visitors to see the work not just as a reproduction of an ancient form but as a cast: an object in its own right with its own unique biography.

Additionally, it is very popular for casts (particularly those in archaeology teaching collections) to be painted to reproduce the material of their original precedent. Casts of bronze sculptures are typically patinated in green/black tones and those made from marble works are often given the colour of milky tea. However, most of the Crawford’s casts retain their pure white Plaster of Paris form, their identities as casts clear and undisguised.

Within the Sculpture Galleries, the plaster material is not something that has to be overlooked in order to access an original piece. In fact, it is celebrated! The casts’ white colour is dramatised by the iconic blue of the gallery walls, making each cast leap out at the viewer from their electrifying backdrop. The whiteness of the plaster is precisely what secures this impact, helping us to realise the casts’ potential as things to look at and not simply look through.

Head of a Little Faun forms the exception to this rule of colour. He does not share the pristine white of the other casts: instead his former top coat is ageing to a muted fawn tone. This, along with the small signs of wear on his surface, further shows how the history of these fascinating objects can often be etched onto their very surfaces.

It was the arrival of the Canova casts in Cork in 1818 that secured the foundation of what was to become Crawford Art Gallery. As a scholar of often-underappreciated reproductions, it brings me great joy that the Gallery and its curators have not forgotten the casts’ fundamental role in their institution’s history. I hope to return to Cork as soon as it is safe to do so and visit these truly inspirational and impactful Galleries once more.

Thank you for joining me on this SCULPTURE SECRETS adventure! If you missed an instalment, the rest of the series can be found here.

Abbey Ellis is a PhD researcher at the University of Leicester and Ashmolean Museum, Oxford on an AHRC CDP placement at Crawford Art Gallery. Her research focuses on archaeological plaster casts, sculptural materials and making, and authenticity.