Research © Dr. Tom Spalding (10.10.2022)

OVERVIEW:

In 1920, Crawford Art Gallery building functioned as the Crawford Municipal School of Art (CMSA), a Free Library and offices for the Cork Borough Technical Instruction Committee, and the residence of two families – a caretaker and the Secretary of the Committee.

Apart from the immediate aftermath of the murder of Lord Mayor of Cork, Tomás MacCurtain (1884-1920) in March 1920, the CMSA remained open throughout the War of Independence and Civil War period.

Evening classes were sometimes curtailed by army curfews. As well as being an educational institution, the CMSA (especially its Lecture Theatre) acted as a home for many civic and voluntary bodies. These activities increased after the burning of Cork’s Municipal Offices in December 1920, although dedicated office space in the School for Cork Corporation was not requisitioned until 1924.

The key influence on the day-to-day life of the building was not the wars (as one might expect), but its existence as a school of art, with its concerns great and small, its annual rhythms, school terms and examinations. Under its Principal, Hugh C. Charde (1858-1946), as well as teaching of full- and part-time art students, the CMSA remained open for exhibitions, scholarship examinations, school tours, concerts throughout this period, suggesting that an attitude of ‘keep calm and carry on’ prevailed amongst the staff. New teachers were recruited (sometimes from the United Kingdom), meetings held, art and materials purchased, and every-day activities continued.

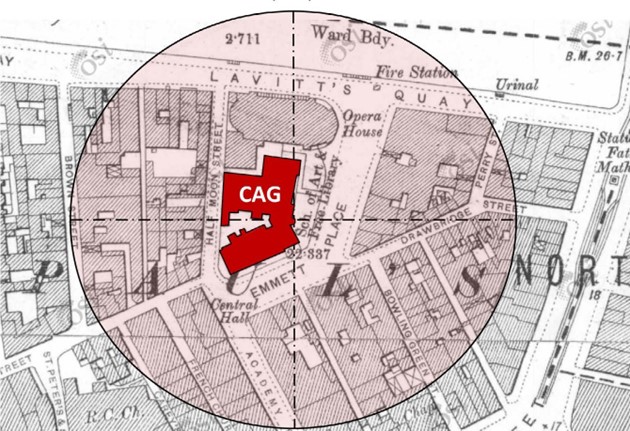

According to the Census of 1911, there were almost 500 people living within a 100-metre radius of the Gallery. There is good reason to believe that most of these were still resident a decade later. The character of the area was residential, as well as industrial and commercial. It was strongly working class.

The Area of Emmett Place

during the War of Independence

and the Civil War,

1920-1923 Unreality and normality

The greatest impression one gets of reading accounts of contemporary life during this period of upheaval was the contrast between the quotidian and the exceptional. While this marks all urban conflict and has provided a rich source of imagery and imagination for writers and artists for many years, it is interesting to consider it in the context of the wars in Cork. Almost all discourse, and the curated material and visual culture of this period concentrates on the military aspects of the conflict: uniforms, military vehicles, weapons, images of physical damage to buildings.

When you drill down into the local newspapers and minutes of the Cork Municipal School of Art building (now the Crawford Art Gallery) and Gibson Bequest Committee (a financial bequest by Joseph Stafford Gibson (1837-1919) which funded much of the acquisitions from 1922), and the city government what becomes apparent is how much everyday life went on.

Interrupted, certainly, but pursued with a dogged, life-affirming attitude to try and continue ‘normality’.

In the Cork Municipal School of Art (CMSA) building (now the Crawford Art Gallery) evening classes continued (sometimes ending early due to curfews), staff were hired (sometimes from England), concerts and public lectures were held in the Lecture Theatre, student ‘socials’ and whist drives were enjoyed and exhibitions were opened in the Picture and Sculpture Galleries.

Due to the burning of Cork City Hall and the Carnegie Library by the British Forces in December 1920, the building also operated as a library and hosted some local government meetings. It was an important centre of civic society in the city for much of this time including a meeting place for the Cork Fever Hospital and Cork Literature and Scientific Society.

The military interruptions in the immediate vicinity of Emmett Place were usually violent, but brief. At least six people were killed in the area. There were a number of lightning British Army raids on local buildings (including on the School of Art in May 1921) and in 1923 the Anti-Treaty faction of the IRA carried out three bomb and gun attacks. Some engagements with violence were of a longer duration. The garage of Johnson & Perrott, which dominated the south side of the square, was effectively an IRA depot for most of 1921 and 1922.

Sometimes violence or ‘historic events’ and events in the Cork Municipal School of Art coincided. For example, during the first annual exhibition of the Munster Fine Art Club; Cork’s Lord Mayor Terence McSwiney (1879-1920) died in Brixton Prison, London, his body was removed to Cork and interred in great state. The show went on. The second exhibition opened eleven days after the signing of the Anglo- Irish Treaty. The 1922-23 autumn School session began in the middle of the Irish Civil War, and, shortly after the death of Michael Collins (1890-1922). The 1923-24 session began shortly after the pro-Treaty faction of the IRA defeated the anti-Treaty IRA the city.

Physical Appearance of Emmett Place, 1922

The area surrounding what is now the Crawford Art Gallery was dominated by industrial and commercial buildings. The little cultural oasis of the Art School and Opera House stood out from the structures surrounding them. Across the square was the premises of Booth & Fox, who made bedding and upholstery. The business was founded in 1825 and exported to the UK and Australia. Its premises burnt in 1955. Behind them were the premises of the British brewers, Bass & Co. As well as beer cellars, the firm owned stables. To the west was the business of Thomas Jennings who stored and aged malt vinegar and made mineral waters. A second mineral water business, Kiloh’s, was situated to the south of the Gallery. There were also ironworks, a confectioners, a print works, pharmaceutical and chemical works, and furniture factories in the immediate area.

Map of Emmett Place area in 1926 by Chas E. Goad Ltd.

KEY: P.H.: Public House. TENS: Tenament Housing GAR: Garage. D: Domestic Residence S: Shop.

The commercial buildings were less prominent, clustered around the south side of Paul Street and on Academy Street and included large grocery warehouses, pawnbrokers and pubs. Only one of the latter (now trading as Cashmans Pub) is still in business. However one of the other local businesses, Johnson & Perrott are still trading, albeit from the Cork suburbs. Founded in 1810 as Johnson’s carriage works, the firm diversified into motor vehicles in the early twentieth century and continue in this business today, although they left Emmett Place in the 2000s.

Cultural Buildings

Though they would have been an important part of life in the area, and the cultural buildings would have been somewhat out of place, Cork Municipal School of Art was a descendant institution of the Cork School of Design, which operated from the 1850s on the ‘South Kensington’ model as a sister school to the Royal College of Art in London. Originally, the School’s premises (a former Customs House, built in 1724) was shared with an organisation called the Royal Cork Institution and was of very modest proportions until its premises were extended in 1884 thanks to a philanthropic donation by William Horatio Crawford (1815-1888). The Art School left Emmett Place, in 1979, and the bulk of the premises were turned over to the Crawford Art Gallery.

Backing onto the Gallery was the Cork Opera House (formerly. ‘Athenaeum’, 1853). This ornate, timber- framed building was cramped and ill-suited to the demands of 1920s productions, but beloved by its audiences for its faded glory and intimate atmosphere. It burned to the ground in 1955.

There was also the Methodist Central Hall used for public events and meetings on Academy St (presently Nando’s restaurant). In addition there were two club houses: the All for Ireland Club (nationalist) at

No.5 (Aroma Chinese restaurant) and the Grafton Club at No. 11 (Starbucks). The makeup of this club’s membership is unclear, but appears to be more pro-British and cultural.

Dwellings

There were a number of lodging houses and hotels in the vicinity of moderate quality. The clientele appears to have consisted of single men, professional or trades men working away from home and theatrical types appearing at the Opera House. As well as this accommodation, there were many tenements in the area subdivided into between three and five flats.

Local people

As the industrial/commercial nature of the area suggests, the vast bulk of the local residents were working class. Based on the 1911 Census returns (the most relevant set available) there were approximately 491 people living within a c.100m radius of the Gallery. There were eighty-four children under ten, and over 100 people between eleven and twenty, but few over sixty, suggesting most people died before they were seventy. The Census of 1921 was abandoned (due to the unsettled nature of the country) and the 1926 Census is not available for consultation yet. Judging by the street directories of Cork, it appears that many of the residents present in 1911 may have still been there in 1921.

Whilst adult literacy was claimed by residents to be almost universal, nearly two thirds of them were working in what can be considered unskilled occupations: carters, labourers, servants, shop staff and factory workers. The largest source of employment was domestic work – either unpaid, as housewives – or paid as lodging-house keepers, domestic servants or laundresses. After that the next largest group (mostly men) were involved in transport of one kind or another, from manually hauling and delivering goods, to driving trams or wagons. A significant group were involved in trades related to retail, either as shop-workers or employed in catering or handicrafts. After that, the next largest group were involved in the building trades, especially plumbing which was a speciality of the area. Very few locals could be considered to be ‘professionals’, e.g. accountants, medics, librarians or teachers.

Typically for Cork, Roman Catholics were a large majority of the population. Also typical is that almost all were born in the city or county of Cork. It was a homogenous, white, Catholic group. Notwithstanding that, there was a significant Protestant minority. This group (about 6%, or three times the present proportion of Protestants in Cork) were almost all working class. This social group has almost completely disappeared from the city in the intervening century. In addition to the local-born community, there were a number of people from other places in Ireland, as well as small numbers of English, German and Scottish residents in 1911. By 1916 there was a tiny Italian community too (see below).

Living Conditions

Due to the nature of the local building stock, over half of the population lived in tenements, probably sharing a single WC and outside tap. Nearly a quarter of people lived in families with only one parent. Only 18% were living in single-occupancy ‘nuclear families’ homes with two parents. Almost as common were cross-generational family units, sometimes with servants, more often with lodgers. Most homes had an adult child living with their parents. It appears that about 30% of children pre-deceased their mothers, but not necessarily in childhood.

Sights, Sounds and Smells

The people of the area would have been used to the sight of workers arriving and leaving the factories and workshops, of theatre-goers, art students (day and evening), city councillors arriving for committee meetings at the School of Art and delivery vehicles (newspaper vans, horse-drawn grocery delivery wagons). The smells of the local area (vinegar, newsprint, beer, hot metal, engine grease, coffee, horse manure and chemicals) would have been obvious to all. The sound of the neighbourhood changed from day (ironworking, the running of engines, theatrical rehearsals, and industrial machinery) to evening (the chatter of theatre-goers leaving the Opera House or in pubs before the curfew or the revving of military lorries and shouted commands in English or Scottish accents, alongside the occasional gunfire or explosion). Given the cramped nature of their living conditions it seems likely that the square was used as a place to socialise and for the younger ones to play games. So we need to add the noise of children’s’ games to our soundscape.

The commercial buildings were less prominent, clustered around the south side of Paul Street and on Academy Street and included large grocery warehouses, pawnbrokers and pubs. Only one of the latter (now trading as Cashmans Pub) is still in business. However one of the other local businesses, Johnson & Perrott are still trading, albeit from the Cork suburbs. Founded in 1810 as Johnson’s carriage works, the firm diversified into motor vehicles in the early twentieth century and continue in this business today, although they left Emmett Place in the 2000s.

Cultural Buildings

Though they would have been an important part of life in the area, and the cultural buildings would have been somewhat out of place, Cork Municipal School of Art was a descendant institution of the Cork School of Design, which operated from the 1850s on the ‘South Kensington’ model as a sister school to the Royal College of Art in London. Originally, the School’s premises (a former Customs House, built in 1724) was shared with an organisation called the Royal Cork Institution and was of very modest proportions until its premises were extended in 1884 thanks to a philanthropic donation by William Horatio Crawford (1815-1888). The Art School left Emmett Place, in 1979, and the bulk of the premises were turned over to the Crawford Art Gallery.

Backing onto the Gallery was the Cork Opera House (formerly. ‘Athenaeum’, 1853). This ornate, timber- framed building was cramped and ill-suited to the demands of 1920s productions, but beloved by its audiences for its faded glory and intimate atmosphere. It burned to the ground in 1955.

There was also the Methodist Central Hall used for public events and meetings on Academy St (presently Nando’s restaurant). In addition there were two club houses: the All for Ireland Club (nationalist) at No.5 (Aroma Chinese restaurant) and the Grafton Club at No. 11 (Starbucks). The makeup of this club’s membership is unclear, but appears to be more pro-British and cultural.

Dwellings

There were a number of lodging houses and hotels in the vicinity of moderate quality. The clientele appears to have consisted of single men, professional or trades men working away from home and theatrical types appearing at the Opera House. As well as this accommodation, there were many tenements in the area subdivided into between three and five flats.

Local people

As the industrial/commercial nature of the area suggests, the vast bulk of the local residents were working class. Based on the 1911 Census returns (the most relevant set available) there were approximately 491 people living within a c.100m radius of the Gallery. There were eighty-four children under ten, and over 100 people between eleven and twenty, but few over sixty, suggesting most people died before they were seventy. The Census of 1921 was abandoned (due to the unsettled nature of the country) and the 1926 Census is not available for consultation yet. Judging by the street directories of Cork, it appears that many of the residents present in 1911 may have still been there in 1921.

Whilst adult literacy was claimed by residents to be almost universal, nearly two thirds of them were working in what can be considered unskilled occupations: carters, labourers, servants, shop staff and factory workers. The largest source of employment was domestic work – either unpaid, as housewives – or paid as lodging-house keepers, domestic servants or laundresses. After that the next largest group (mostly men) were involved in transport of one kind or another, from manually hauling and delivering goods, to driving trams or wagons. A significant group were involved in trades related to retail, either as shop-workers or employed in catering or handicrafts. After that, the next largest group were involved in the building trades, especially plumbing which was a speciality of the area. Very few locals could be considered to be ‘professionals’, e.g. accountants, medics, librarians or teachers.

Typically for Cork, Roman Catholics were a large majority of the population. Also typical is that almost all were born in the city or county of Cork. It was a homogenous, white, Catholic group. Notwithstanding that, there was a significant Protestant minority. This group (about 6%, or three times the present proportion of Protestants in Cork) were almost all working class. This social group has almost completely disappeared from the city in the intervening century. In addition to the local-born community, there were a number of people from other places in Ireland, as well as small numbers of English, German and Scottish residents in 1911. By 1916 there was a tiny Italian community too (see below).

Living Conditions

Due to the nature of the local building stock, over half of the population lived in tenements, probably sharing a single WC and outside tap. Nearly a quarter of people lived in families with only one parent. Only 18% were living in single-occupancy ‘nuclear families’ homes with two parents. Almost as common were cross-generational family units, sometimes with servants, more often with lodgers. Most homes had an adult child living with their parents. It appears that about 30% of children pre-deceased their mothers, but not necessarily in childhood.

Sights, Sounds and Smells

The people of the area would have been used to the sight of workers arriving and leaving the factories and workshops, of theatre-goers, art students (day and evening), city councillors arriving for committee meetings at the School of Art and delivery vehicles (newspaper vans, horse-drawn grocery delivery wagons). The smells of the local area (vinegar, newsprint, beer, hot metal, engine grease, coffee, horse manure and chemicals) would have been obvious to all. The sound of the neighbourhood changed from day (ironworking, the running of engines, theatrical rehearsals, and industrial machinery) to evening (the chatter of theatre-goers leaving the Opera House or in pubs before the curfew or the revving of military lorries and shouted commands in English or Scottish accents, alongside the occasional gunfire or explosion). Given the cramped nature of their living conditions it seems likely that the square was used as a place to socialise and for the younger ones to play games. So we need to add the noise of children’s’ games to our soundscape.

Thirteen Lives

As a way of accessing the lives of these people and their experiences (not all military) during the period 1920-1923, we shall look at thirteen local people in a little detail. Their age and dates follow their names

- William Horgan, Aged 21 in 1921. (Cork, 1900 – Cork, 1921).

Dillon’s Cross, Mayfield. Fireman with the Great Southern &Western Railway. Killed aged 21 by the Belgian-born, 2nd Lt Adelin Eugene van Outryve d’Ydewalle of the South Staffordshire Regt. on Lavitt’s Quay on 28th Jun, 1921. One of six children of Richard and Annie Horgan, Dillon’s Cross.

- Lt Adelin Eugene van Outryve d’Ydewalle was also in command of the group of soldiers responsible for the death of Vol. Daniel Spriggs on Blarney St on 8th Jul 1921.

- Charles McCarthy, Justice of the Peace, 62, (Cork, 1859 – Cork, 1939)

Proprietor of Plumbing Business, 2, Emmett Pl. Heavily involved in Cork institutions including the School of Art. Paid for a Mass to be offered for ‘the heroic’ Terence McSwiney, Sep 1920.

- Ran the largest of the four plumbing businesses in immediate area in 1916. In addition, two other households included a plumber.

- Francis Bonaventure Giltinan, 43 (Cork, c.1878 – Cork, 1938)

Resident at the School of Art with his family and maid. Secretary of the County Borough of Cork Technical Instruction Committee since 1898. Lost wife and daughter in rapid succession, April 1921. His new-born daughter, Mary, was premature and died at home, and his wife, also Mary, died nine days later of ‘pernicious anaemia’. Giltinan continued to work throughout. He moved across Emmett Place to Mrs Long’s lodging house at No.4 (see below) with his surviving son Donal by 1924. He remarried. A hardworking public servant ‘who never spared himself’ and became the first CEO of the Cork Vocational Education Committee in 1930.

- Catherine Long, 74, (Cork, c.1847 - Cork, 1931)

Shopkeeper, 3 & 4 Emmett Pl, (Presently Donut shop) Lived with her and son, and daughter, who ran a lodging house. Her premises appears to adjacent to (and/or below) the All for Ireland Club (see above). This clubhouse was associated with William O’Brien’s All for Ireland League, a nationalist organisation. It was raided by Crown Forces, 25th Sep 1920, but nothing was found. In 1922 it was used as a meeting place by IRA brigade staff.

y5.OD’BerliieanM, 1a6 or 17, (Cork, c.1905 - ?)

5 or 6, Emmett Pl. Injured by shrapnel in anti-Treaty IRA attack on Johnson & Perrott Garage on the night of 22nd Sep 1922. The total injured was: 4 soldiers and 2 girls. The second injured girl was a Miss Morrissey from nearby Cornmarket St.

- Seamus Fitzgerald, 25, (Queenstown [An Cóbh], 1896 – Cork, 1972)

TD in 1st Dáil, served in ‘A’ Coy, 4th Batt, Cork No.1 Brigade. Anti-Treaty. In 1921, the Dáil Éireann publicity department which he oversaw, was located in the School of Art, where ‘one day Crown Forces completely surrounded the building and captured all our records and equipment, but

we ourselves escaped through a back way into the opera house. The loss of our records was a tremendous blow to us and I was considerably worried as the original signed depositions were included amongst them.’ This appears to have happened in May 1921.

- Harry (Joshua Henry) Scully RHA, 62, (Cork City, c.1859 – London, 1935).

Lived above ‘Grattan Club’, 11, Emmett Pl in 1911 (Starbucks), which he appears to have operated as an artist’s teaching studio. Left Ireland during the war of Independence or Civil War and moved to Orpington, Kent.

- Frank J (James Francis) Pitt, age unknown. (Herefordshire, - London, 1938)

1, Victoria Ave, Blackrock Rd. Impresario, manager and secretary of Cork Opera House from 1912 to 1938. Member of the Grafton Club (see below). His house contents were burnt in an attempted arson attack, (probably by the Anti-Treaty IRA) 18th Apr, 1923. This was possibly in retaliation for his holding a National (i.e. pro-Treaty) Army charity boxing tournament the previous month, and the frequency of British performers and material presented at the Cork Opera House in the previous three years. He was married with one daughter, and his wife, Margaret was at home when the arson attack happened.

- Denis Whelan, 50, (Co. Laois, c.1861 - Cork, 1928)

Constable RIC (ret’d), 5, Half-moon St. His son, Séan Ó Faoláin, served in the IRA and was anti- Treaty. Ó Faoláin describes him as a an imperialist to the core ‘in his dark bottle-green uniform, black leather belt with brass buckle, black helmet or peaked cap, black truncheon case and black boots.’

- John Buckley, c.71, (Cork, c. 1850 – Cork, 1939)

Operated an ‘Art Iron Works’ from 6 or 7, Half-moon St. Buckley’s works supplied railings to business premises (shops, pubs) as well as to UCC (Mardyke grounds), Crawford Municipal Technical Institute. His son, Sgt D Buckley, was in the Royal Engineers and was injured in 1915.

- William George Simpson, 20, (Cork, 1901 – Cork, 1968?)

Previous resident of Grafton Club, where his mother, Kate was Steward. His step-father was a highly-decorated Sergeant in the Royal Irish Regiment, died in 1919, at Fermoy. A Constable Wm Simpson (possibly the same man) of the RIC was injured during the IRA raid on Midleton RIC Barracks, 28th Dec 1920.

- Annie Horgan, (neé Collins), 31, (Bantry, c.1887 – Cork, 1958)

Vintner, (23 Academy St, AKA 1, Paul St – i.e. Cashman’s Pub). Took out a licence on an Arnott & Co. (later Murphy’s) tied house in her early 1920s and ran it with her younger sister, Katie. It was not unusual for a young woman to be operating a pub, and she had probably worked at a barmaid

at another pub beforehand. Married Maurice Horgan, 1914. Annie gave up the bar between 1925 and 1930, whereupon Katie continued to run it until at least 1958

- Enerico (Endrick) Lucchesi, 44, (Italy, c.1877 - ?)

Proprietor, ‘fried fish & chip potato shop’, 17, Drawbridge St (currently ‘Samui’). From at least 1907, Enerico and his brother Giocondo (Italy, 1887 - Cork, 1955) were ‘figure makers’ (makers of statuary) at 16, Oliver Plunkett St. Their father was called Gustavo and they seem to have arrived in Cork c.1905, and had branched out into late-night fish and chips by 1912.

a. By 1916 there was a small Italian Irish community in the Crawford Art Gallery area namely: the Lombardis at 27, Paul St (Fish & Chips) and the well-established Bernardi family at 39, Paul

St (statue makers since the 1870s). In 1911, the family of Quirino Fulignati (French polisher and Cabinet maker) lived on Henry St, but they appear to have moved to Kyle St by 1923, and operated a furniture workshop on Brown St, off Paul St from the early 1930s, by which time they were also running a fish & chip shop on Robert St.